|

Yule, The Winter Solstice

Yule: the Winter Solstice, Yuletide (Teutonic), Alban Arthan (Caledonii)

Around

Dec. 21

This Sabbat represents the rebirth of light. Here, on the longest night of the year, the Goddess gives birth to

the Sun God and hope for new light is reborn.

Yule is a time of awakening to new goals and leaving old regrets behind.

Yule coincides closely with the Christian Christmas celebration. Christmas was once a movable feast celebrated many different

times during the year. The choice of December 25 was made by the Pope Julius I in the fourth century AD because this coincided

with the pagan rituals of Winter Solstice, or Return of the Sun. The intent was to replace the pagan celebration with the

Christian one.

The Christian tradition of a Christmas tree has its origins in the Pagan Yule celebration. Pagan families

would bring a live tree into the home so the wood spirits would have a place to keep warm during the cold winter months. Bells

were hung in the limbs so you could tell when a spirit was present.

Food and treats were hung on the branches for the spirits

to eat and a five-pointed star, the pentagram, symbol of the five elements, was placed atop the tree.

The colors of the

season, red and green, also are of Pagan origin, as is the custom of exchanging gifts.

A solar festival, The reindeer stag

is also a reminder of the Horned God. You will find that many traditional Christmas decorations have some type of Pagan ancestry

or significance that can be added to your Yule holiday. Yule is celebrated by fire and the use of a Yule log. Many enjoy the

practice of lighting the Yule Log. If you choose to burn one, select a proper log of oak or pine (never Elder). Carve or chalk

upon it a figure of the Sun (a rayed disc) or the Horned God (a horned circle). Set it alight in the fireplace at dusk, on

Yule. This is a graphic representation of the rebirth of the God within the sacred fire of the Mother Goddess. As the log

burns, visualize the Sun shining within it and think of the coming warmer days. Traditionally, a portion of the Yule Log is

saved to be used in lighting next year's log. This piece is kept throughout the year to protect the home.

www.geocities.com/athens/olympus/4643/yule.html

Yule: A Traditional Pagan Holiday

Jennifer Gilbert

jboop69@bellatlantic.net

Yule is one of the four minor Sabbats; it celebrates the rebirth of the Sun and the Sun God and honors the Horned

God. It is celebrated between December 20 and 22; the exact date varies from year to year depending on when the Sun reaches

the southern most point in its yearly cycle. The longest night of the year falls on Yule; it is when we celebrate the coming

light and thank the Gods for seeing us through the darkness. It is a time to look on the past year's achievements and to celebrate

with family and friends.

This day is the official first day of winter. The Goddess gives birth to the Sun Child and hope for new light is

born. Yule is also known as the Winter Solstice, Alban Arthan, Finn's Day, Festival of Sol, Yuletide, Great Day of the Cauldron,

and Festival of Growth. The origins of most of the Christian Christmas traditions are in the Pagan Yule celebration, such

as the Christmas tree, the colors red and green and gift-giving.

Whether you're designing a pagan or Wiccan ritual, want to incorporate some truly traditional elements into your

holiday celebrations, or are just curious, the following are natural elements associated with Yule for many years.

Symbols used to represent Yule are evergreen trees, yule logs, holly, eight-spoked wheels, wreaths, and spinning

wheels.

Traditional foods for the Yule feast are roasted turkey, caraway rolls, mulled wine, dried fruit, egg nog, pork,

beans, and gingerbread people.

The plants and herbs associated with Yule are holly, mistletoe, evergreens, poinsettia, tropical flowers, bay,

pine, ginger, myrrh, valerian.

For Yule incense and oil, you can use any of the following scents, either blended together or alone: rosemary,

myrrh, nutmeg, saffron, cedar/pine, wintergreen, ginger, bayberry.

Colors associated with Yule are red, green, white, gold.

Stones associated with Yule are bloodstone, ruby, garnet, cat's eye.

Animals and mythical beasts associated with Yule are stags, squirrels, wrens/robins, phoenix, trolls, memecolion.

Appropriate Yule Goddesses are all Spinning Goddesses. Some Yule Goddesses are:

Angerona (Roman),

Eve (Hebraic),

Pandora (Greek),

Zvezda (Slavic),

Metzli (Aztec),

Yachimato-Hime (Japanese),

Tiamat (Babylonian),

NuKua (Chinese)

Appropriate Yule Gods are all Re-Born Sun Gods. Some Yule Gods are:

Apollo (Greco-Roman),

Balder (Norse),

Oak/Holly King (Anglo-Celtic),

Ra (Egyptian),

Saturn (Roma),

Jesus (Christian-Gnostic),

Helios (Greek),

Ukko (Finnish-Yugoritic).

Altar decorations may include mistletoe, holly, a small Yule log, strings of colored lights, Yule/Christmas cards,

a candle in the shape of Kris Kringle, a homemade wreath, presents wrapped in colorful paper.

Traditional activities during Yule are decorating the Yule tree, exchanging gifts, storytelling, making wreaths,

throwing holiday parties, sending greetings.

Taboos on Yule are extinguishing fire and traveling.

Spell work can be for divination, a healthier planet, peace, joy.

http://uufnorthiowa.org/Special _Projects/paganyule2002/paganyule.htm

Medieval Christmas Traditions

Among the Pagan traditions that have become part of Christmas is burning the yule log. This custom springs from

many different cultures, but in all of them its significance seems to lie in the iul or "wheel" of the year. The Druids would

bless a log and keep it burning for 12 days during the winter solstice; part of the log was kept for the following year, when

it would be used to light the new yule log. For the Vikings, the yule log was an integral part of their celebration of the

solstice, the julfest; on the log they would carve runes representing unwanted traits (such as ill fortune or poor honor)

that they wanted the gods to take from them.

Wassail comes from the Old English words waes hael, which means "be well," "be hale," or "good health." A strong,

hot drink (usually a mixture of ale, honey, and spices) would be put in a large bowl, and the host would lift it and greet

his companions with "waes hael," to which they would reply "drinc hael," which meant "drink and be well." Over the centuries

some non-alcoholic versions of wassail evolved.

Other customs developed as part of Christian belief. For example, Mince Pies (so called because they contained

shredded or minced meat) were baked in oblong casings to represent Jesus' crib, and it was important to add three spices (cinnamon,

cloves and nutmeg) for the three gifts given to the Christ child by the Magi. The pies were not very large, and it was thought

lucky to eat one mince pie on each of the twelve days of Christmas (ending with Epiphany, the 6th of January).

Food

The ever-present threat of hunger was triumphantly overcome with a feast, and in addition to the significant fare

mentioned above, all manner of food would be served at Christmas. The most popular main course was goose, but many other meats

were also served. Around 1520 turkey was first brought to Europe from the Americas, and because it was inexpensive and quick

to fatten, it rose in popularity as a Christmas feast food.

Humble (or 'umble) pie was made from the "humbles" of a deer -- the heart, liver, brains and so forth. While the

lords and ladies ate the choice cuts, the servants baked the humbles into a pie (which of course made them go further as a

source of food). This appears to be the origin of the phrase, "to eat humble pie." By the seventeenth century Humble Pie had

become a trademark Christmas food, as evidenced when it was outlawed along with other Christmas traditions by Oliver Cromwell

and the Puritan government.

The Christmas pudding of Victorian and modern times evolved from the medieval dish of frumenty -- a spicy, wheat-based

dessert. Many other desserts were made as welcome treats for children and adults alike.

Christmas Trees and Plants

The tree was an important symbol to every Pagan culture. The oak in particular was venerated by the Druids. Evergreens,

which in ancient Rome were thought to have special powers and were used for decoration, symbolized the promised return of

life in the spring and came to symbolize eternal life for Christians. The Vikings hung fir and ash trees with war trophies

for good luck.

In the middle ages, the Church would decorate trees with apples on Christmas Eve, which they called "Adam and Eve

Day." However, the trees remained outdoors. In sixteenth-century Germany, it was the custom for a fir tree decorated with

paper flowers to be carried though the streets on Christmas Eve to the town square, where, after a great feast and celebration

that included dancing around the tree, it would be ceremonially burned.

Holly, ivy, and mistletoe were all important plants to the Druids. It was believed that good spirits lived in the

branches of holly. Christians believed that the berries had been white before they were turned red by Christ's blood when

He was made to wear the crown of thorns. Ivy was associated with the Roman god Bacchus and was not allowed by the Church as

decoration until later in the middle ages, when a superstition that it could help recognize witches and protect against plague

arose.

Entertainment

Christmas may owe its popularity in medieval times to liturgical dramas and mysteries presented in the church.

The most popular subject for such dramas and tropes was the Holy Family, particularly the Nativity. As interest in the Nativity

grew, so did Christmas as a holiday.

Carols, though very popular in the later middle ages, were at first frowned on by the Church. But, as with most

popular entertainment, they eventually evolved to a suitable format, and the Church relented.

The Twelve Days of Christmas may have been a game set to music. One person would sing a stanza, and another would

add his own lines to the song, repeating the first person's verse. Another version states it was a Catholic "catechism memory

song" that helped oppressed Catholics in England during the Reformation remember facts about God and Jesus at a time when

practicing their faith could get them killed. (If you would like to read more about this theory, please be warned that it

contains graphic descriptions of the violent nature in which Catholics were executed by the Protestant government and has

been refuted as an Urban Legend.)

Pantomimes and mumming were another form of popular Christmas entertainment, particularly in England. These casual

plays without words usually involved dressing up as a member of the opposite gender and acting out comic stories.

In pagan times different woods were burned to produce different effects:

Aspen: invokes understanding of the grand design

Birch: signifies new beginnings

Holly: inspires visions and reveals past lives

Oak: brings healing, strength, and wisdom

Pine: signifies prosperity and growth

Willow: invokes the Goddess to achieve desires

www.stcharleschristmas.com/yulelog.htm

http://historymedren.about.com/library/blxmas.htm

Solstice Celebration - Saturnalia

From N.S. Gill

Saturnalia

In

Ancient Rome, the mythical age of Saturn's kingship was a golden

age of happiness for all men, without theft or servitude,

and without

private property. Saturn, dethroned by his son Jupiter, had joined

Janus as ruler in Italy, but when his

time as earthly king was up, he

disappeared. "It is said that to this day He lies in a magic sleep on

a secret island

near Britain, and at some future time ... He will

return to inaugurate another Golden Age."

Janus instituted the Saturnalia

as a yearly tribute to his friend,

Saturn. For mortals, the festival provided a yearly symbolic return

to the Golden

Age. It was an offense during this period to punish a

criminal or start a war. The meal normally prepared only for the

masters was prepared and served first to the slaves, and in further

reversal of the normal order, it was served to

the slaves by the

masters.

All people were equal and, because Saturn ruled before the current

cosmic order,

Misrule, with its lord (Saturnalia Princeps), was the

order of the day.

Children and adults exchanged gifts, but the

adult exchange became so

great a problem -- the rich getting richer and the poor getting

poorer -- that a law was

enacted making it legal only for richer

people to give them to poorer.

According to Macrobius' Saturnalia, the

holiday was originally

probably only one day, although he notes an Atellan playwright,

Novius, described it as being

seven days. With Caesar's changing the

calendar, the number of days of the festival increased.

©2007 About, Inc.,

All rights reserved.

http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/holidaysfestivals/a/solsticeceleb_2

.htm

Yule

by Yvonne Rathbone

©2000

The Sun King is born! Long live the Sun King!

Tree - Alder

First day of Winter

Sun at 0° Capricorn

December 21

Themes: beginnings, birth, family, being ready for winter, light, Sun.

There is a special symbolism in the fact that after Yule the days get longer and winter gets

colder. The Goddess is still a crone and so the Earth is still asleep. Yet the God is reborn, the days are longer. Before

the hardest season, where we must struggle to survive, we are reminded of birth.

The God is born at Yule. Some say he is conceived at Yule to be born at Imbolc. Regardless,

these are only metaphors. The God at Yule passes through the veil back to the side of the living. He comes out of the Summerlands

just as the Sun returns from its farthest point.

The rituals around Yule bear an uncanny resemblance to Christmas. I believe that Yule must

have been one of the most important holidays to many of the European Pagans taken over by Christian rule. The holiday was

lifted whole cloth apparently, the names were changed to protect the very powerful church, but the symbolism is there. The

main difference is that in the Pagan traditions it is understood that the God will die and be reborn again and again.

Rituals at this time focus on the rebirth of the God and the Return of the Sun. All night vigils

during the longest night with sunrise "services" are a very powerful way to connect again with the cycles of the Earth. Meditations

on the fertile space of conception. Remembering family, whom you'll need and who will need you in order to get through winter.

The Yule log was originally a pagan custom for bringing in greenery during this most dead of

times. Often the Yule log was burned and one piece saved to protect the house for the rest of the year. This remnant was then

used to light the next year's log.

The tree I chose for Yule is the Alder. The Alder sends out its seeds on the wind and is the

first tree to return after a forest fire. Even now on the northern slopes of Mount Saint Helen's, Alder trees are growing

again, holding the soil together and fixing in nitrogen. (Alders are one of the few plant species outside of the Bean Family

to do this.) The Alder tree is truly a tree of rebirth. In winter we can see its small flowers - hope for the coming year.

There are two types of Alder native to California and commonly seen around the Bay Area. They are the Red alder and the White

Alder.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

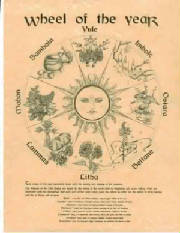

| "Wheel of the Year" |

|

| Artwork by Mickie Mueller |

Midwinter's Eve:

YULE

by Mike Nichols

Our Christian friends are often quite surprised at how enthusiastically we Pagans celebrate the

‘Christmas’ season. Even though we prefer to use the word “Yule”, and our celebrations may peak a

few days before the twenty-fifth, we nonetheless follow many of the traditional customs of the season: decorated trees,

caroling, presents, Yule logs, and mistletoe. We might even go so far as putting up a ‘Nativity set’, though for

us the three central characters are likely to be interpreted as Mother Nature, Father Time, and the baby Sun God. None of

this will come as a surprise to anyone who knows the true history of the holiday, of course.

In fact, if truth be known, the holiday of Christmas has always been more Pagan than Christian, with its associations

of Nordic divination, Celtic fertility rites, and Roman Mithraism. That is why John Calvin and other leaders of the Reformation

abhorred it, why the Puritans refused to acknowledge it, much less celebrate it (to them, no day of the year could be more

holy than the Sabbath), and why it was even made illegal in Boston! The holiday was already too closely associated

with the birth of older Pagan Gods and heroes. And many of them (like Oedipus, Theseus, Hercules, Perseus, Jason, Dionysus,

Apollo, Mithra, Horus, and even Arthur) possessed a narrative of birth, death, and resurrection that was uncomfortably close

to that of Jesus. And to make matters worse, many of them predated the Christian Savior.

Ultimately, of course, the holiday is rooted deeply in the cycle of the year. It is the winter solstice that

is being celebrated, seedtime of the year, the longest night and shortest day. It is the birthday of the new Sun King, the

Son of God—by whatever name you choose to call him. On this darkest of nights, the Goddess becomes the Great Mother

and once again gives birth. And it makes perfect poetic sense that on the longest night of the winter, “the dark night

of our souls”, there springs the new spark of hope, the Sacred Fire, the Light of the World, the Coel Coeth.

That is why Pagans have as much right to claim this holiday as Christians. Perhaps even more so, since the Christians

were rather late in laying claim to it, and tried more than once to reject it. There had been a tradition in the West that

Mary bore the child Jesus on the twenty-fifth day, but no one could seem to decide on the month. Finally, in 320 C.E., the

Catholic fathers in Rome decided to make it December, in an effort to co-opt the Mithraic celebration of the Romans, the Yule

festival of the Saxons, and the midwinter revels of the Celts.

There was never much pretense that the date they finally chose was historically accurate. Shepherds just don’t

“tend their flocks by night” in the high pastures in the dead of winter! But if one wishes to use the New Testament

as historical evidence, this reference may point to sometime in the spring as the time of Jesus’ birth. This is because

the lambing season occurs in the spring and that is the only time when shepherds are likely to “watch their flocks by

night”—to make sure the lambing goes well. Knowing this, the Eastern half of the church continued to reject December

25, preferring a “movable date” fixed by their astrologers according to the moon.

Thus, despite its shaky start (for over three centuries, no one knew when Jesus was supposed to have been born!),

December 25 finally began to catch on. By 529, it was a civic holiday, and all work or public business (except that of cooks,

bakers, or any that contributed to the delight of the holiday) was prohibited by the Emperor Justinian. In 563, the Council

of Braga forbade fasting on Christmas Day, and four years later the Council of Tours proclaimed the twelve days from December

25 to Epiphany as a sacred, festive season. This last point is perhaps the hardest to impress upon the modern reader, who

is lucky to get a single day off work. Christmas, in the Middle Ages, was not a single day, but rather a period of

twelve days, from December 25 to January 6. The Twelve Days of Christmas, in fact. It is certainly lamentable that

the modern world has abandoned this approach, along with the popular Twelfth Night celebrations.

Of course, the Christian version of the holiday spread to many countries no faster than Christianity itself,

which means that “Christmas” wasn’t celebrated in Ireland until the late fifth century; in England, Switzerland,

and Austria until the seventh; in Germany until the eighth; and in the Slavic lands until the ninth and tenth. Not that these

countries lacked their own midwinter celebrations. Long before the world had heard of Jesus, Pagans had been observing the

season by bringing in the Yule log, wishing on it, and lighting it from the remains of last year’s log. Riddles were

posed and answered, magic and rituals were practiced, wild boars were sacrificed and consumed along with large quantities

of liquor, corn dollies were carried from house to house while caroling, fertility rites were practiced (girls standing under

a sprig of mistletoe were subject to a bit more than a kiss), and divinations were cast for the coming spring. Many of these

Pagan customs, in an appropriately watered-down form, have entered the mainstream of Christian celebration, though most celebrants

do not realize (or do not mention it, if they do) their origins.

For modern Witches, Yule (from the Anglo-Saxon yula, meaning “wheel” of the year) is usually

celebrated on the actual winter solstice, which may vary by a few days, though it usually occurs on or around December 21.

It is a Lesser Sabbat or Low Holiday in the modern Pagan calendar, one of the four quarter days of the year, but a very important

one. Pagan customs are still enthusiastically followed. Once, the Yule log had been the center of the celebration. It was

lighted on the eve of the solstice (it should light on the first try) and must be kept burning for twelve hours, for good

luck. It should be made of ash. Later, the Yule log was replaced by the Yule tree but, instead of burning it, lighted candles

were placed on it. In Christianity, Protestants might claim that Martin Luther invented the custom, and Catholics might grant

St. Boniface the honor, but the custom can demonstrably be traced back through the Roman Saturnalia all the way to ancient

Egypt. Needless to say, such a tree should be cut down rather than purchased, and should be disposed of by burning, the proper

way to dispatch any sacred object.

Along with the evergreen, the holly and the ivy and the mistletoe were important plants of the season, all symbolizing

fertility and everlasting life. Mistletoe was especially venerated by the Celtic Druids, who cut it with a golden sickle on

the sixth night of the moon, and believed it to be an aphrodisiac. (Magically—not medicinally! It’s highly toxic!)

But aphrodisiacs must have been the smallest part of the Yuletide menu in ancient times, as contemporary reports indicate

that the tables fairly creaked under the strain of every type of good food. And drink! The most popular of which was the “wassail

cup”, deriving its name from the Anglo-Saxon term waes hael (be whole or hale).

Medieval Christmas folklore seems endless: that animals will all kneel down as the Holy Night arrives, that

bees hum the 100th psalm on Christmas Eve, that a windy Christmas will bring good luck, that a person born on Christmas Day

can see the Little People, that a cricket on the hearth brings good luck, that if one opens all the doors of the house at

midnight all the evil spirits will depart, that you will have one lucky month for each Christmas pudding you sample, that

the tree must be taken down by Twelfth Night or bad luck is sure to follow, that “if Christmas on a Sunday be, a windy

winter we shall see”, that “hours of sun on Christmas Day, so many frosts in the month of May”, that one

can use the Twelve Days of Christmas to predict the weather for each of the twelve months of the coming year, and so on.

Remembering that most Christmas customs are ultimately based upon older Pagan customs, it only remains for modern

Pagans to reclaim their lost traditions. In doing so, we can share many common customs with our Christian friends, albeit

with a slightly different interpretation. And, thus, we all share in the beauty of this most magical of seasons, when the

Mother Goddess once again gives birth to the baby Sun God and sets the wheel in motion again. To conclude with a long-overdue

paraphrase, “Goddess bless us, every one!”

www.geocities.com/athens/forum/7280/yule.html

Deities of the Winter Solstice

From Patti Wigington

While

it may be mostly Pagans and Wiccans who celebrate the Yule

holiday, nearly all cultures and faiths have some sort of winter

solstice celebration or festival. Because of the theme of endless

birth, life, death, and rebirth, the time of the

solstice is often

associated with deity and other legendary figures. No matter which

path you follow, chances are

good that one of your gods or goddesses

has a winter solstice connection.

Alcyone (Greek): Alcyone is the Kingfisher

goddess. She nests every

winter for two weeks, and while she does, the wild seas become calm

and peaceful.

Ameratasu

(Japan): In feudal Japan, worshippers celebrated the return

of Ameratasu, the sun goddess, who slept in a cold, remote

cave.

When the the other gods woke her with a loud celebration, she looked

out of the cave and saw an image of herself

in a mirror. The other

gods convinced her to emerge from her seclusino and return sunlight

to the universe.

Balder

(Norse): Balder is associated with the legend of the

mistletoe. His mother, Frigga, honored Baldur, asked all of nature

to

promise not to harm him. Unfortunately, in her haste, Frigga

overlooked the mistletoe plant, so Loki – the

resident trickster –

took advantage of the opportunity and fooled Baldur's blind twin,

Hod, into killing him

with a spear made of mistletoe. Baldur was

later restored to life.

Bona Dea (Roman): This fertility goddess was

worshipped in a secret

temple on the Aventine hill in Rome, and only women were permitted to

attend her rites. Her

annual festival was held early in December.

Cailleach Bheur (Celtic): In Scotland, she is also called Beira, the

Queen

of Winter. She is the hag aspect of the Triple Goddess, and

rules the dark days between Samhain and Beltaine.

Demeter (Greek): Through her daughter, Persephone, Demeter is

linked

strongly to the changing of the seasons and is often connected to the

image of the Dark Mother in winter. When

Persephone was abducted by

Hades, Demeter's grief caused the earth to die for six months, until

her daughter's return.

Dionysus

(Greek): A festival called Brumalia was held every December

in honor of Dionysus and his fermented grape wine. The event

proved

so popular that the Romans adopted it as well.

Frigga (Norse): Frigga honored her son, Baldur, by asking

all of

nature not to harm him, but in her haste overlooked the mistletoe

plant. Loki fooled Baldur's blind twin, Hod,

into killing him with a

spear made of mistletoe but Odin later restored him to life. As

thanks, Frigga declared that

mistletoe must be regarded as a plant of

love, rather than death.

Holly King (British/Celtic): The Holly King

is a figure found in

British tales and folklore. He is similar to the Green Man, the

archetype of the forest. In modern

Pagan religion, the Holly King

battles the Oak King for supremacy throughout the year. At the winter

solstice, the

Holly King is defeated.

Horus (Egyptian): Horus was one of the solar deities of the ancient

Egyptians. He rose

and set every day, and is often associated with

Nut, the sky god. Horus later became connected with another sun god,

Ra.

La

Befana (Italian): This character from Italian folklore is similar

to St. Nicholas, in that she flies around delivering

candy to well-

behaved children in early January. She is depicted as an old woman on

a broomstick, wearing a black

shawl.

Lord of Misrule (British): The custom of appointing a Lord of Misrule

to preside over winter holiday festivities

actually has its roots in

antiquity, during the Roman week of Saturnalia.

Odin (Norse): In some legends, Odin bestowed

gifts at Yuletide upon

his people, riding a magical flying horse across the sky. This legend

may have combined with that of St. Nicholas

to create the modern

Santa Claus.

Saturn (Roman): Every December, the Romans threw a week-long

celebration

of debauchery and fun, in honor of their agricultural

god, Saturn. Roles were reversed, and slaves became the masters,

at

least temporarily. This is where the tradition of the Lord of Misrule

originated.

Spider Woman (Hopi):

Soyal is the Hopi festival of the winter

solstice. It honors the Spider Woman and the Hawk Maiden, and

celebrates

the sun's victory over winter's darkness.

©2007 About, Inc., All rights reserved.

http://paganwiccan.about.com/od/yulethelongestnight/a/Winter_Sol_Gods.

htm?nl=1

History of Yule

From Patti Wigington

A Festival of Light:

Many cultures have winter festivals that are in fact celebrations of

light. In addition to Christmas, there's Hannukah

with its brightly

lit menorahs, Kwanzaa candles, and any number of other holidays. The

holiday called Yule takes place

on the day of the winter solstice,

around December 21. On that day (or close to it), an amazing thing

happens in the

sky. The earth's axis tilts away from the sun in the

Northern Hemisphere, and the sun reaches at its greatest distance

from the equatorial plane. As a festival of the Sun, the most

important part of any Yule celebration is light -- candles,

bonfires,

and more.

Origins of Yule:

In the Northern hemisphere, the winter solstice has been celebrated

for

millenia. The Norse peoples viewed it as a time for much

feasting, merrymaking, and, if the Icelandic sagas are to be

believed, a time of sacrifice as well. Traditional customs such as

the Yule log, the decorated tree, and wassailing

can all be traced

back to Norse origins.

Celtic Celebrations of Winter:

The Celts of the British Isles celebrated

this midwinter holiday as

well. Although little is known about the specifics of what they did,

many traditions persist.

According to the writings of Julius Caesar,

this is the time of year in which Druid priests sacrificed a white

bull

and gathered mistletoe in celebration.

Roman Saturnalia:

Few cultures knew how to party like the Romans. Saturnalia

was a

festival of general merrymaking and debauchery held around the time

of the winter solstice. This week-long party

was held in honor of the

god Saturn, and involved sacrifices, gift-giving, special privileges

for slaves, and a lot

of feasting. Although this holiday was partly

about giving presents, more importantly, it was to honor an

agricultural

god.

Welcoming the Sun Through the Ages:

Four thousand years ago, the Ancient Egyptians took the time to

celebrate

the daily rebirth of Horus - the god of the Sun. As their

culture flourished and spread throughout Mesopotamia, other

civilizations decided to get in on the sun-welcoming action. They

found that things went really well... until the

weather got cooler,

and crops began to die. Each year, this cycle of birth, death and

rebirth took place, and they

began to realize that every year after a

period of cold and darkness, the Sun did indeed return.

Winter festivals

were also common in Greece and Rome, as well as in

the British Isles. When a new religion called Christianity popped up,

the new hierarchy had trouble converting the Pagans, and as such,

folks didn't want to give up their old holidays.

Christian churches

were built on old Pagan worship sites, and Pagan symbols were

incorporated into the symbolism of

Christianity. Within a few

centuries, the Christians had everyone worshipping a new holiday

celebrated on December

25.

In some traditions of Wicca and Paganism, the Yule celebration comes

from the Celtic legend of the battle between

the young Oak King and

the Holly King. The Oak King, representing the light of the new year,

tries each year to usurp

the old Holly King, who is the symbol of

darkness. Re-enactment of the battle is popular in some Wiccan

rituals.

©2007

About, Inc., All rights reserved.

http://paganwiccan.about.com/od/yulethelongestnight/p/Yule_History.htm

| "Drawing Down the Moon" |

|

| Artwork by Mickie Mueller |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|